What Is Course Acceleration?

Course acceleration describes the process of transforming a traditional, online or face-to-face 16-week semester course into a shorter course format, typically eight or less weeks in length or compressed 25% or more (Pastore, 2010).

Accelerated courses maintain the same level of academic integrity and course rigor but are “presented in less time than the traditional number of contact hours” (Wlodkowski, 2003). As stated in Wlodkowski and Westover (1999), the accelerated course format has been critiqued for valuing “convenience over substance and rigor” (pg. 3).

However, the research focused on accelerated online courses explains that learner satisfaction, learning effectiveness, achievement of learning outcomes, instructor ratings, and student retention are not negatively impacted by the compressed courses (Anderson & Anderson, 2012; Austin & Gustafson 2006; Carman & Bartsch, 2017; Eames, et al., 2018; Kucsera & Simaro, 2010; Vlachopoulos, et al., 2019; Shaw, et al., 2013; Sheldon & Durdella, 2009; Wlodkowski & Westover, 1999). In fact, some studies reveal that students enrolled in Education, Business, and Nursing accelerated courses score higher in capstone courses and on exit exams than students enrolled in the equivalent traditional course modalities (Thorton, et al., 2017).

What Is Not Course Acceleration?

If you have an existing online course of traditional length, it can be tempting to simply compact existing content into an accelerated structure. While utilizing existing content after thoughtfully examining alignment to course and program standards is encouraged, only compacting content can negatively impact the student experience and may feel disjointed for the online accelerated learner as it is not delivered in a format that is tailored to their course length and specific needs (Boyd, 2007).

A learning outcome-focused course “potentially creates opportunities to plan more effectively to teach in compressed formats. Instructors can focus on what needs to be learned and plan accordingly” (Kops, 2014, pg. 3).

By using this model, accelerated courses shift from lecturing to facilitating. A change to a compressed course format requires a paradigm shift for instructors as well as students. There are mutual responsibilities to make an accelerated course work effectively. Key areas for an accelerated course are the inclusion of great interaction, significant self-learning, and increased responsibility (Marques, 2012, pg. 103).

Students enrolled in successful accelerated courses have indicated that certain teaching methods make for a more successful learning experience including active learning, classroom interaction and discussion, and a clear, purposeful course organization (Scott, 2003, pg. 32). In accelerated courses where these methods were used, students reported that they experienced “more concentrated, focused learning, more collegial, comfortable classroom relationships, more memorable experiences, more in-depth discussion, less procrastination, and stronger academic performances” (Scott, 2003, pg. 32).

Course acceleration is a multi-step process that requires you to deconstruct previous course content to reconstruct it in a new, accelerated format. Consider some or all of the following steps to help you accelerate your course.

Identify the Course-Level Objectives (COs) that have been used in previous, traditional-length versions of the course. Ask the following questions as you review and revise. (Note: Sometimes, COs are set by the program and cannot be revised by the faculty member. Please check with your program lead before revising.)

- Are these COs aligned with the program-level outcomes? If they are not, revise the COs to ensure alignment with the course’s program outcomes.

- Do these COs reflect what you want your students to be able to do, say, or know at the conclusion of the course?

- Are the COs written with measurable verbs that reflect digital learning standards?

- Are the COs relevant to workforce skills and practices? Do they describe activities that students will need to be able to complete once they have joined the workforce? If they are not reflective of workforce expectations, consider revising the COs to include that important alignment.

These questions are important for the course acceleration process as they help you understand how your course fits in the program and align all content tightly to those program outcomes. These objectives will also help you determine which content to include (and exclude) in later steps of course acceleration.

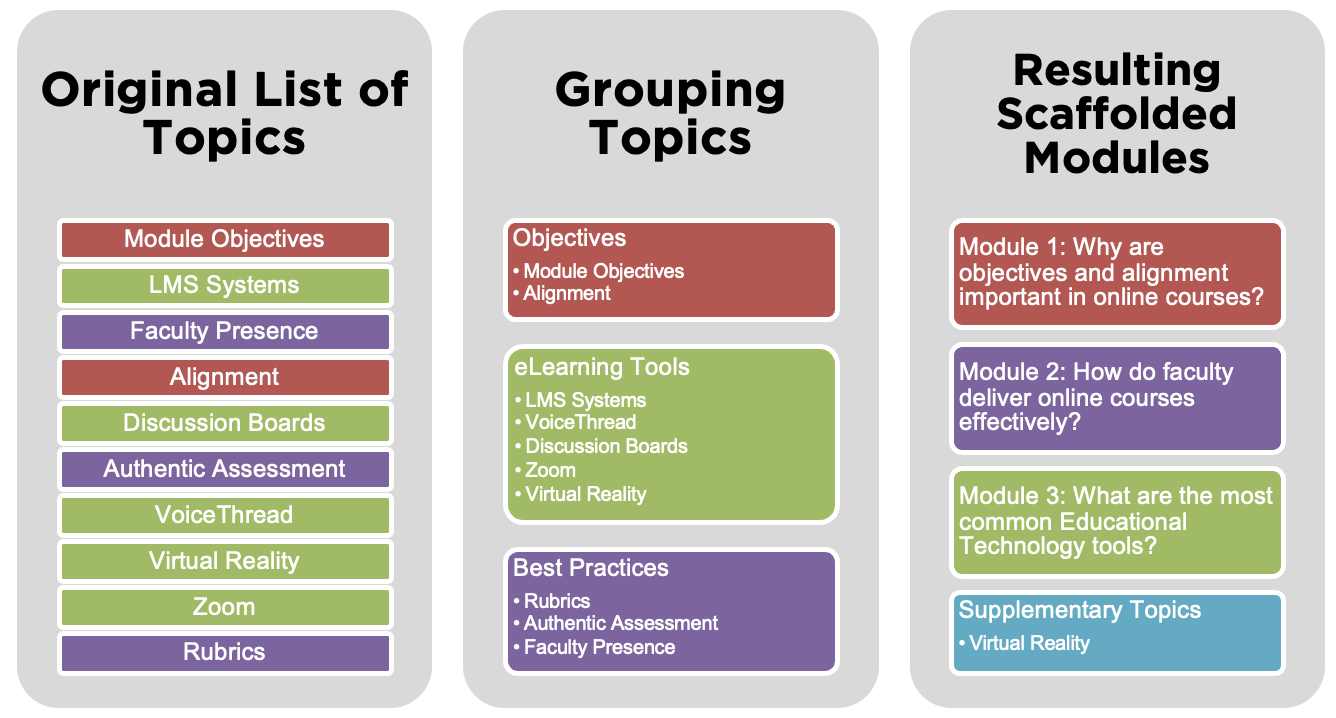

You’ll want to consider listing out all the main topics found in your course as a means of helping you craft your module objectives and identify course flow. You may already have this list if you taught this course previously, or you may need to create this list. The easiest way to do this is to review your COs and list out the most important topics that are embedded within those overarching COs. Next, identify topics that may overlap or complement one another and group them together. If you already have a list of topics from a previous time you taught, be sure that your topics align in some fashion with your COs. Once groups have been identified, organize them so concepts build on one another from topic to topic and across the course continuum. This can become the flow of the course, week over week. Here’s an example:

During this step, if you started with an already developed list of topics, you may also identify some that do not align with Course Objectives. Are these need to know or nice to know topics for students? If they are need to know, you may consider including an additional Course Objective to ensure alignment. If they are nice to know, you may consider creating a “Supplementary Resources” area in the course or within each module. Or they really might not be as relevant as you initially thought and can be removed entirely. Considering the nice and need to knows help you to more tightly align all your content to the essential learning objectives, and thus help you to shorten the course length while retaining all the necessary information and content for students.

If this course has been taught previously, you will likely have already constructed Module Objectives (MOs) that accompanied your topics. MOs should specify an observable behavior, skill, or action in small, discrete pieces. Think of MOs as building blocks or tasks that lead student to mastery of a Course Objective. Now that course topics have been reorganized and potentially been marked as supplementary, MOs will now need to undergo the same process. Organize your MOs to the correct topic. Then, ask yourself the following questions as you review and revise:

- Are these MOs aligned with the Course Objectives? Note that MOs can align to one or more COs. If not, be sure to revise the MOs to ensure alignment with the COs.

- Do these MOs reflect what you want your students to be able to do, say, or know at the conclusion of the module?

- Are the MOs written with measurable verbs that reflect digital learning standards?

- Are the MOs relevant to workforce skills and practices? Do they describe activities that students will need to be able to complete once they have joined the workforce?

You may find that some of the MOs are no longer relevant to the course as the topic has been moved to supplementary or it was never aligned to a CO. In this case, the MOs can be removed from the course. Alternatively, you may find that you have some topics from your list that are left over and don’t align to any MOs. You can either remove those topics or create a new MO for them.

If this course has not been taught previously, take this time to craft MOs. Each module will likely have between 5-7 MOs, although you may find more or less are necessary depending on the topic and activities students will complete.

This reflective period is important for course acceleration as it helps you understand how each module fits in the course. These objectives will also help you determine which assessments and course content to include (and exclude) in later steps of course acceleration.

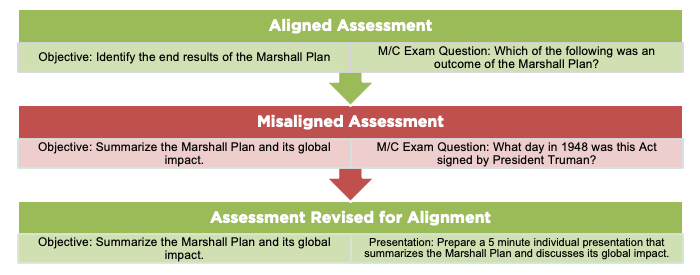

At this point, you may have now revised your COs and streamlined your topics. Due to these revisions, you may find that that any previous assessments you used for this course might need to be reviewed and revised to maintain alignment to the learning objectives. Consider the following questions as you review each assessment:

- Is this assessment aligned with at least one module-level outcome? Be sure you have indicated which objective it is aligned with.

- For all aligned assessments, do the measurable verbs included in the MOs match what the students remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, or create in the assessment? You may find that you need to either (1) revise the MO to better align with the assessment used in the course or (2) revise the assessment to align to the MO.

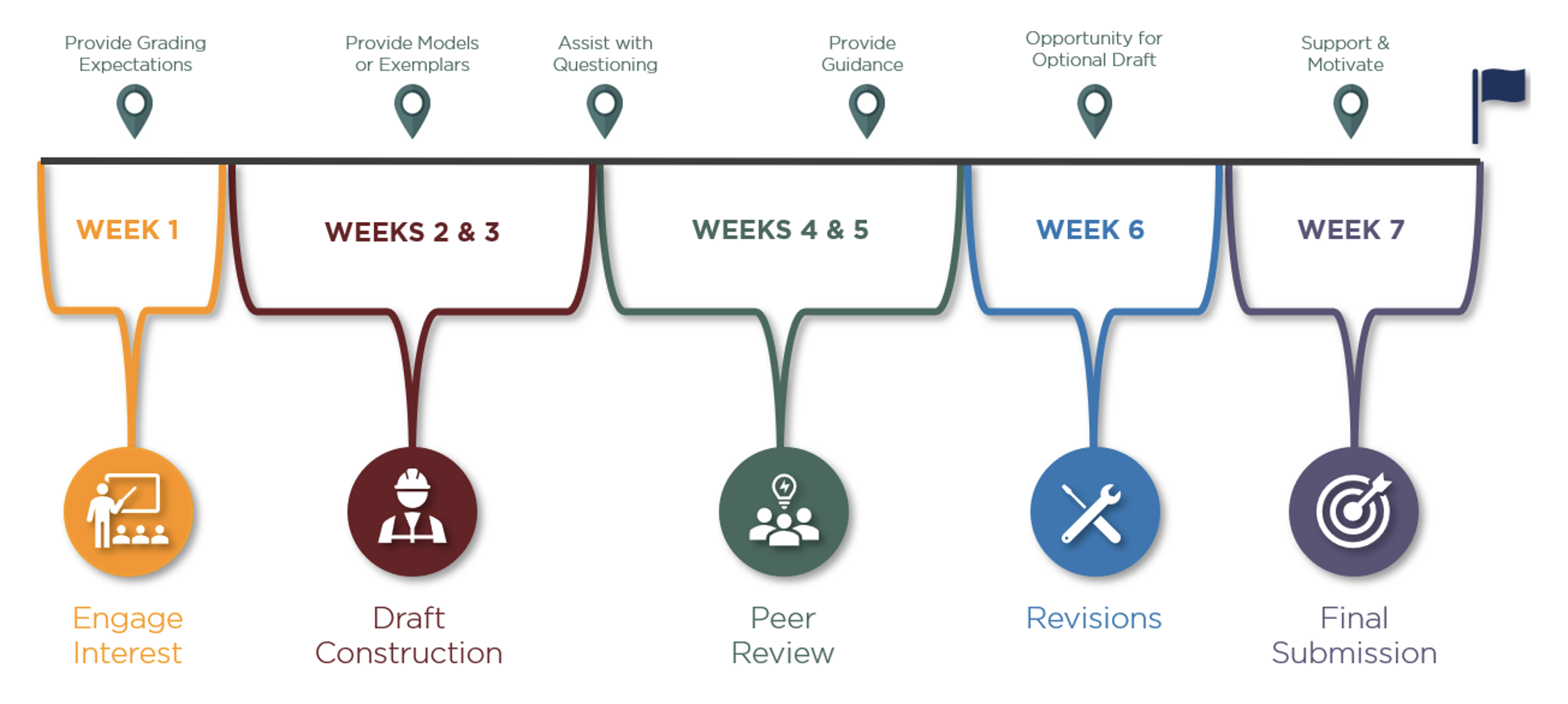

You should now have a clear list of aligned assessments in your course and have a great handle on the alignment of your very targeted course objectives. However, you may have noticed that some of your assessments require too much student time-on-task in a given week to be able to complete it. Consider scaffolding, or breaking assessments into parts that build upon each other, in order to even out student workload and better manage your own workload for grading. For major assessments, consider the following:

- Are there opportunities for students to practice their learning or draft an assessment before submitting a major exam, project, or presentation?

- Do students have the chance to practice with the Educational Technology required for the major assessment? For example, if students submit a 30-minute final presentation via a recording, can they create practice presentations for feedback or complete videos in other, low-stakes ways?

- Do students interact with one another’s work for this assessment? Are there peer review opportunities?

- Is a larger assessment in the course too lengthy for a student to reasonably complete in an accelerated format? Are there areas of the assessment that can be broken into smaller pieces that can be assessed earlier?

- Have you given yourself enough time to provide students quality feedback? Feedback should be timely and substantive, especially on larger assessments. A maximum of 72 hours of wait time is generally suggested for feedback.

If the answer to any of these questions is “no,” consider revising the current assessment for scaffolding. Here is an example of how you might scaffold a large, final assessment like a Research Paper.

Reading through these different suggestions of accelerating your course, you may have started to reflect on your workload for grading. Have you required numerous, lengthy writing assignments? Are all assignments individual? If you feel that the current aligned assessments may impact your ability to provide regular and substantive feedback for your students, consider some of the below revisions:

- Utilize Auto-Graded Knowledge Checks: Auto-graded MC Quizzes, Games, Flash Cards, and other tools provide students an opportunity to practice and track their progress without requiring written feedback from you.

- Provide Rubrics, Grading Expectations, and Exemplars: When students can familiarize themselves with expectations for a larger assessment, they are less likely to ask a lot of questions about the assignment or require substantial feedback or a potential resubmission. Rubrics in your LMS can also autocalculate grades, provide pointed feedback, and provide you with the opportunity to easily comment on a variety of criteria. An exemplar assignment showing students exactly what you expect for a submission from students will also help reduce the workload on you. Consider providing both a good exemplar as well as a bad exemplar for students to see the continuum of work quality.

- Encourage Self- and Peer-Review: Self- and Peer-Review of major assessments can also help students understand expectations and compare their work to their peers. These opportunities can be especially valuable if the students are provided with rubrics or guiding questions to help steer them in the right direction.

- Include Partner and Group Assessments: When possible, consider asking students to partner up or work within small groups. While this does reduce the number of items to grade, it does require careful consideration and planning.

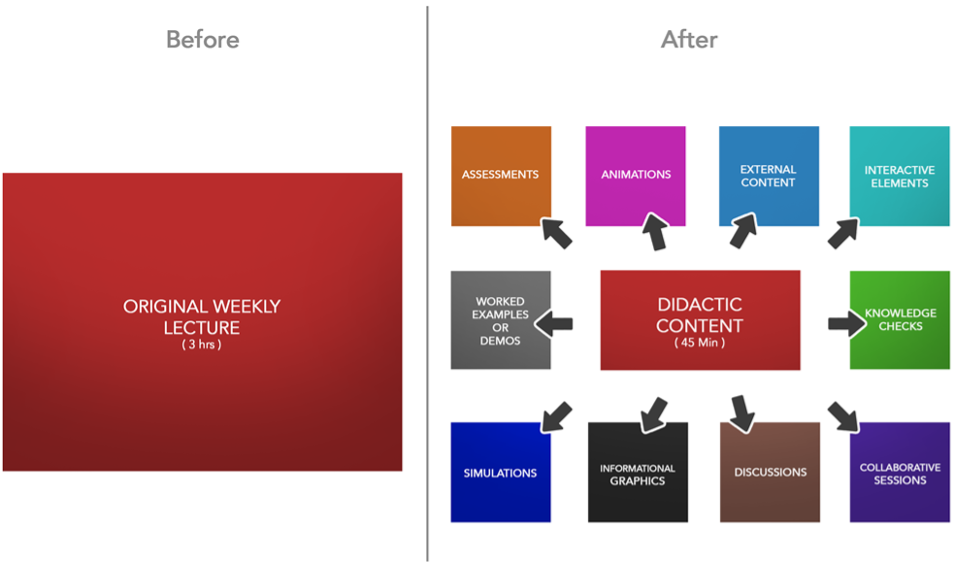

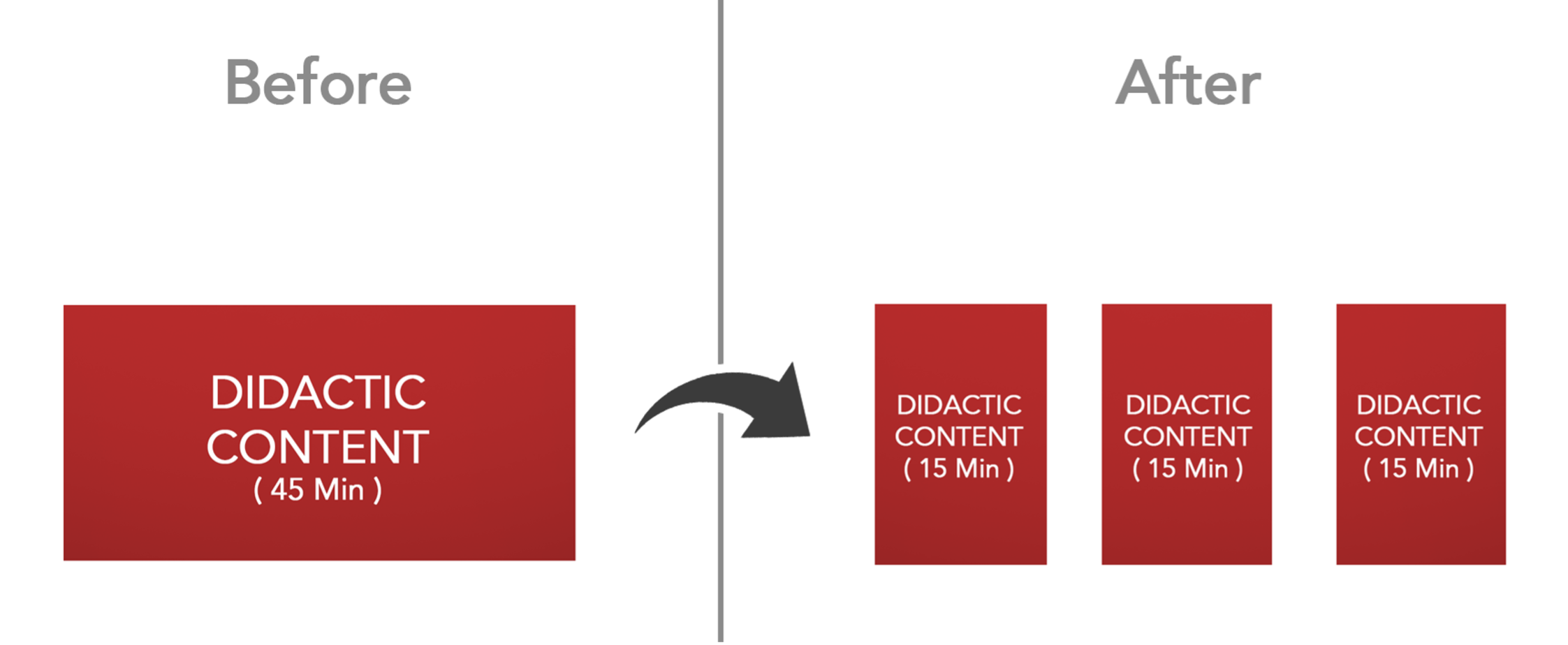

Transitioning a course from a traditional format to an online, accelerated course requires some optimization of didactic, or learning, content for optimal delivery and a high-quality student experience. This is especially important to create a consistent structure that is easier for students to follow week over week, providing students with opportunities for short learning experiences that can more easily fit into an adult’s busy schedule, and ensuring that content is appropriately scaffolded for learners to more easily understand and retain the new information. The online medium provides many new, multisensory opportunities not available in traditional learning content such as a lecture. Reducing and segmenting didactic content helps reduce learner fatigue, decreases satiation, and can increase learning performance.

While some content may need to be provided in a recorded lecture-style video, you want to be very selective about what you choose to record. Consider and extrapolate the times in your traditional lecture when you interact with your face-to-face students. The moments below can be provided to students in another method outside of a recorded video.

- When do you pause for reflection?

- When do you ask the students to hypothesize an outcome?

- Are there moments when you draw diagrams on the board, visit websites, tell personal stories, or show a demonstration?

- When are students asked to interact with one another?

In the example below, the lecture content is originally 3 hours; however, after reflecting on alternative means of content delivery, only 45 minutes of lecture content needs to be recorded. 2 hours and 15 minutes are delivered through alternate means.

Like you did earlier with your topics, you’ll also want to consider alignment and the nice to know vs need to know. As you distill lectures and decide on content, ask if the item is need to know or nice to know for your students. If a piece of content is redundant or not aligned with an objective, it is nice to know and should be provided as a supplementary or optional resource. Remember, the goal here is to optimize while retaining necessary information for students. Consider utilizing a variety of alternative delivery methods as you optimize.

With all of your pieces ready for acceleration, it’s time to consider module organization. Using a logical order for your content that is consistent across modules can help students easily navigate the course, decrease confusion, and provide structure. It also helps to alleviate cognitive load as students know exactly where to go and what to do. Some areas of consistency include the order of content, the flow of activities, and the due dates. For example, each module might begin with an introduction video and brief written discussion of the module objectives. Then, course readings are provided alongside optimized lecture content. After reviewing all materials, students might be asked to complete a knowledge check quiz and post to a small group discussion board. Then, students spend the rest of the module responding to discussion posts and working on their individual assessments. Each week is then concluded with a self-reflection and an anonymous student survey to track progress.

Organization and chunking help our brains more easily retain the content in front of us. Consider this example:

In this image, various shapes of different sizes and colors are displayed. If you were asked to reproduce this image after viewing it for 30 seconds, how close would your recreation be? Now consider this image:

In this image, the content has been “chunked” by shape, color, and size. How much easier would it be to reproduce that image after 30 seconds?

No matter the organizational structure you select for your course, remaining consistent is key.

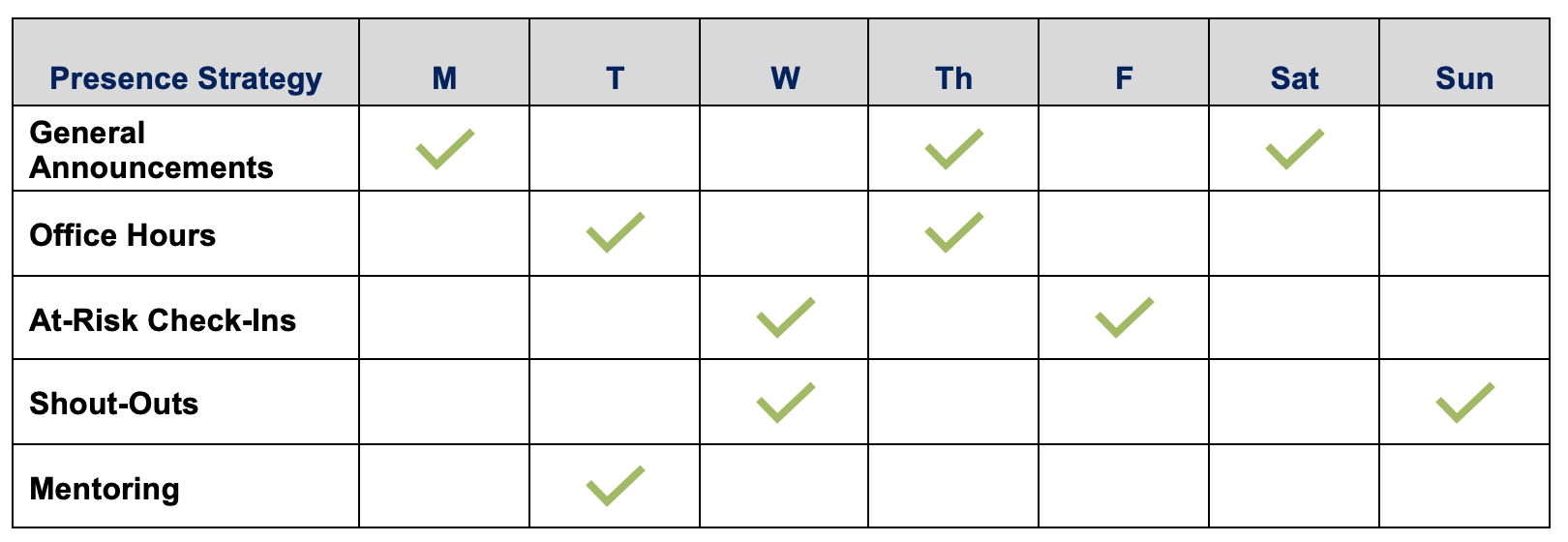

Accelerated courses move quickly and require additional consideration for delivery. The first few weeks of the course are especially vital as students can fall behind quickly in accelerated course formats. Crafting a plan for instructor presence will be vital for each week of the course. You’ll want to plan opportunities for reaching out to the larger class and moments where individual students may need specialized attention. Here is an example of how you might schedule weekly delivery opportunities:

Larger course communications, like announcements, can be pre-written or drafted to save time during the delivery period. During delivery, utilize gradebook data and course analytics like logins to help you determine when individual students may need extra support. Consider using a course journal to capture notes about the delivery of the course. What patterns do you see week over week, course offering over course offering? Consider crafting an FAQ for the most commonly asked questions. Additionally, take note of the feedback you find yourself giving over and over and save that in a Word document that you can use in the future to save some time. Planning for delivery can help you to best support students at critical moments throughout an accelerated course.

No matter the presence plan you design for your course, remaining consistent is key. Consistency for due dates will also help students plan weeks in advance and help avoid any missed submissions. Don’t forget that utilizing weekend hours for your working adult learners can help them spread their workload across seven days. Here is an example of how you might keep dates consistent in your course:

Activity | Day & Time (Institution’s Time Zone) |

Modules Begin | Mondays, 12:01 am |

Knowledge Checks Due | Wednesdays, 11:59 pm |

Discussion Board Initial Posts Due | Thursdays, 11:59 pm |

Discussion Board Responses Due | Sundays, 11:59 pm |

Self-Reflections Due | Sundays, 11:59 pm |

Major Assessments Due | Sundays, 11:59 pm |

Modules Ends | Sundays, 11:59 pm |

Congratulations! Using some or all of the suggestions provided here, you broke each of your major course items into their component parts, considered measurability and alignment, revised assessments for scaffolding and scale, optimized lecture components, and created a consistent structure for your course. You should now have most of the items you need to begin building your course in the Learning Management System.

References

- Anderson, T. I. & Anderson, R. J. (2012). Time compressed delivery for quantitative college courses: The key to student success. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 16(S1), S55.

- Austin, A. M. & Gustafson, L. (2006). Impact of Course Length on Student Learning. Journal of Economics and Finance Education, 5(1), 26–37. http://www.economics-finance.org/jefe/econ/Gustafsonpaper.pdf

- Boyd, D. (2007). Effective teaching in accelerated learning programs. Adult Learning, 15(1-2), 40-43. doi:10.1177/104515950401500111

- Carman, C. A. & Bartsch, R. A. (2017). Relationship Between Course Length and Graduate Student Outcome Measures. Teaching of Psychology, 44(4), 349–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628317727912

- Eames, M., Luttman, S., Parker, S. (2018). Accelerated vs. traditional accounting education and CPA exam performance. Journal of Accounting Education 44(1). DOI: 10.1016/j.jaccedu.2018.04.004

- Kops, W. G. (2014). Teaching Compressed-Format Courses: Teacher-Based Best Practices. Canadian Journal of University Continuing Education, 40(1), 1-18, http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/cjuce-rcepu.

- Kucsera, J.V., Zimaro, D. (2010). Comparing the Effectiveness of Intensive and Traditional Courses, College Teaching, 58:2, 62-68, DOI: 10.1080/87567550903583769

- Marques, J. (2012). The Dynamics of Accelerated Learning. Business Education & Accreditation, 4 (1). 101-112. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2005248.

- Pastore, R. S. (2010). The effects of diagrams and time-compressed instruction on learning and learners’ perceptions of cognitive load. Educational Technology Research and Development, 58(5), 485-505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-009-9145-6

- Scott, P. (2003). Attributes of high-quality accelerated courses. In R. J. Wlodkowski & C. E. Kasworm (Eds.), Accelerated learning for adults: The promise and practice of intensive educational formats [special issue]. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 97, 29-38. doi: 10.1002/ace.86

- Shaw, M., Chametzky, B., Burns, S. W., & Walters, K. J. (2013). An Evaluation of Student Outcomes by Course Duration in Online Higher Education. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 16(4), 1–33.

- Sheldon, C. Q. & Durdella, N.R. (2009). Success rates for students taking compressed and regular length developmental courses in the community college. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 34:1-2, 39-54, DOI: 10.1080/10668920903385806

- Thornton, B., Demps, J., & Jadav, A. (2017). Reduced Contact Hour Accelerated Courses and Student Learning. Journal of Instructional Pedagogies, 18. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1151741.pdf

- Vlachopoulos, P., Jan, S. K., Lockyer, L. (2019). A comparative study on the traditional and intensive delivery of an online course: design and facilitation recommendations. Research in Learning Technology 27. DOI: 10.25304/rlt.v27.2196

- Wlodkowski, R.J. & Westover, T.N. (1999). Accelerated Courses as a Learning Format for Adults. Canadian journal for the study of adult education, 13, 1-20.

- Wlodkowski, R. J. (2003). Accelerated learning in colleges and universities. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2003(97), 5-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.84