Table of Contents

Discussion Boards in Quantitative Education

Why focus on discussion boards for teaching quantitative concepts? “College graduates may have bachelor’s degrees in arts or sciences but need to exhibit strong critical thinking, analytical, writing, and oral communication skills,” says Beth Reiland, Chief Personnel Officer for the Exeter Group. Reiland argues that the kinds of core skills tested on the GMAT quantitative section are the necessary building blocks of problem-solving but emphasizes that having these analytical skills is not sufficient. Workplaces need individuals who can communicate effectively with each other about quantitative issues. “In the business consulting environment, we come up with better solutions using collaborative thinking processes,” Reiland explains. “Solutions to complex problems are improved by working in cooperative groups: sharing assumptions and information, thinking aloud about approaches, and testing ideas with others.” Therefore, Reiland continues, educators need to “devote energies to developing a clear language for communicating about quantitative topics.” (Source: Taylor, C. (2008). Preparing Students for the Business of the Real (and Highly Quantitative) World. Calculation vs. Context, 109.)

Regarding the use of discussion boards amongst undergraduate business students, Tsai and Tsai (2013) identified four distinct conceptions of online argumentation: (1) reflecting on and extending ideas, (2) negotiating ideas, (3) expressing ideas, and (4) discussing ideas. They also identified four approaches to online argumentation: (1) evaluating postings making careful reflections (2) getting responses for enhancing understanding, (3) replying to postings and adding to ideas, and (4) finding the related information.

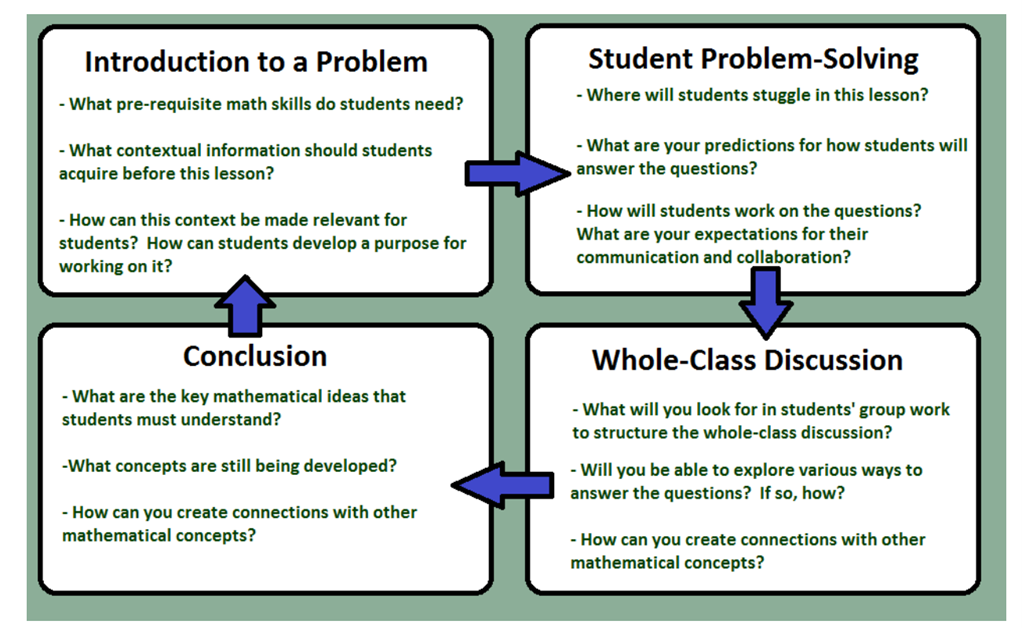

Developing student understanding of quantitative reasoning skills requires a classroom that promotes communication, collaboration, and persistence in problem-solving. Regarding the development of conceptual understanding in college-level quantitative reasoning courses, Hiebert and Grouws (2007) find that:

- Students need to be provided with ongoing opportunities to learn.

- Deep understanding means forming connections between facts, ideas, and procedures in a social/cultural setting.

- Making connections between mathematical concepts should be an explicit focus of students and teachers and is a product of active discourse.

- Teachers provide opportunities to learn by allowing students to struggle with grasping important concepts.

- Promoting conceptual understanding also means promoting skill fluency.

- Class discussions provide opportunities to form explicit connections between mathematical concepts, and an instructor-led conclusion supports those connections.

Online discussion boards allow students to build on one another’s thinking by providing examples, correcting when necessary, or connecting to already existing knowledge. The discussion process provides students with validation from peers, which builds their confidence in statistical thinking throughout the thinking process.

Collaborative learning is particularly helpful in statistics education. Technology can facilitate and promote collaborative exploration and inquiry, allowing students to generate their own knowledge of a concept or new method in a constructivist learning environment. Group interactions have an important role in questioning and critiquing individual perspectives in a mutually supportive fashion so that a clear understanding of statistical concepts, energy, and knowledge of statistical ideas develops. Research has shown that it is essential to discuss the output and results with the students and require them to provide explanations and justifications for the conclusions they draw from the output and to be able to communicate their conclusions effectively.

Source: http://www.ohiohighered.org

Design Strategies

- Incorporate an external math-friendly asynchronous (or synchronous) whiteboard system to create “cooperative bulletin boards,” where, for example, each student contributes one step, in a different color, to solving an equation. Thus, students model problem-solving for each other.

- Allow guest experts and field practitioners to participate in the course by posting information & responding to questions from students.

- Focusing on current events is a great way to use discussion boards. Students can read or listen to news stories about current topics and discuss their views on the discussion boards. In addition, they can practice their writing skills by creating their own articles and editorials.

- Jump-start discussion by drawing from the following list of question types:

- Exploratory: Probe facts and basic knowledge.

- Challenge: Interrogate assumptions, conclusions, or interpretations.

- Relational: Ask for comparisons of themes, ideas, or issues.

- Diagnostic: Probe motives or causes.

- Action: Call for a conclusion or action.

- Cause and Effect: Ask for causal relationships between ideas, actions, or events.

- Extension: Expand the discussion.

- Hypothetical: Pose a change in the facts or issues.

- Priority: Seek to identify the most important issues.

- Summary: Elicit synthesis.

Facilitation Strategies

- Give students clear expectations about online discussion requirements, deadlines, and grading procedures.

- Assess the quality as well as the quantity of the students’ online posts. Using rubrics will allow students to have clear guidelines of your expectations for quality of their posts.

- Provide a schedule of upcoming discussion board deadlines for students. Give as much notice as possible.

- Provide the structure for students to post to threads. A good structure lessens the frustration of what to write.

- Make yourself visible in the discussion. Students will be more likely to engage in the discussion if they see you are part of it.

Regular and Substantive Feedback

Assessing quantitative reasoning skills involves judging written analyses and reflections on the quality of evidence given in support of arguments or conclusions. To effectively communicate and evaluate student understanding of such skills, feedback should include commentary regarding:

- Evidence supporting reasoning or assertions

- Calculations that produce numerical results

- Correct units on quantities

- Complete and correct sentences stating evidence and conclusions

- Precision of language in stating questions and results

Strong instructor engagement with students combats the misimpression that online classes “teach themselves.” In online courses, students often want the instructor to serve as the guide, facilitator, and teacher even more so than in the face-to-face classroom.

Practice proactive course management strategies such as monitoring assignment submissions, communicating and reminding students of missed and/or upcoming deadlines, and making course progress adjustments in response to student concerns.

Remember that many learners are professionals returning to the classroom. They may be unaccustomed to the online learning environment. Increased faculty to student engagement can reduce the sense of isolation online students may feel. Without face-to-face contact, faculty cannot observe nonverbal cues that could indicate that students are frustrated, unenthusiastic, anxious, or confused.

Consider taking weekly polls or surveys within the class to learn which parts of the content may be troubling for students. Consider adding a “Muddiest Point” discussion area where students can post questions at any time to receive peer feedback in addition to feedback from the instructor and assistant staff.

Build a sustaining “learning partnership” with students through a combination of improved instructor presence and rapport. Both techniques are shown to foster student engagement in the online learning environment.

Presence in an online course context is understood as the ability of people “to project their personal characteristics into the community, thereby presenting themselves to other participants as real people.” Consider adding videos which show you explaining a concept to students in addition to videos and/or audio recordings of your lectures.

Rapport is the establishment of a sense of personal connection in relationships that is characterized by mutual understanding and communication. Research indicates that in classes where teachers established rapport, students were more likely to pay attention to new subject matter, thereby increasing motivation and engagement.

If you find it too difficult to address each student individually each week, consider establishing time to interact with groupings of students to share your personal experiences and insights into the concepts discussed in the course. Through shared interaction, the instructor serves as a model for the discourse and a learning facilitator by providing students with constructive critique and ongoing formative feedback.

Best practices regarding faculty-student interactions include:

- Clearly delineated course requirements

- Clear and adequate guidance

- Multiple communication modes

- Continuous, supportive feedback

Remember the acronym VOCAL (Visible, Organized, Compassionate, Analytical, and Leader-by-example) when planning your student engagement strategy:

Visible: Visibility is closely linked to the concept of social presence. In a face-to-face classroom where students and the instructor meet in the same place at the same time for a shared experience, there is a high degree of two-way visibility. The online classroom differs largely because written feedback replaces face-to-face, verbal communication, often leading students to feel as if the instructor is not actively participating. This makes it more likely for the students to adopt a passive role or become unresponsive, leading to lower levels of meaningful learning. Suggested strategies to counteract the perceived lack of visibility focus on the instructor’s visibility being actively demonstrated through public and private communication channels.

Organized: Online learners generally choose to take online courses, assuming these will provide more flexibility for their busy schedules. Because of this, they need to clearly understand what is expected of them so they can plan and organize their time in order to meet course requirements efficiently. This increased time management responsibility on the part of the learner also means that there is an increased organizational responsibility on the part of the online instructor. To meet the needs of students, instructors must plan to offer multiple touchpoints to enhance student learning and ensure that the learning outcomes have been achieved. Scheduled meetings with students and frequent ungraded “knowledge check” quizzes are helpful touchpoints.

Compassionate: Adult often choose an online format because of the conditions and challenges they face in the real world, including personal and professional commitments. Instructors need to be responsive by demonstrating compassion and understanding toward their students’ needs. This can be accomplished by providing access and permission to communicate directly in mutually suitable ways (i.e., by email, by phone, by Skype); reminding students of expectations related to course participation; and responding timeously and directly to student problems and/or concerns.

Analytical: Management on the part of instructors includes the timely return of assignments and the evaluation and grading of student work. While Canvas LMS provides tools for assessment and analysis, it is ultimately the instructor’s responsibility to determine whether the form of the assessment is appropriate, meaningful, and relevant. Suggested strategies include clear expectations and detailed guidelines for assignments and transparency of grading through the use of detailed rubrics.

Leader-by-Example: Online instructors set the tone for student performance, and instructors should model best practice strategies that will meaningfully engage students and guide the overall learning experience. There are a variety of ways in which instructors can model appropriate online learning and behavior. These actions may include an initial synchronous introduction or weekly synchronous chat during which the instructor provides clear and helpful responses to any questions or concerns. Model responsibility and accountability by returning assignments and grades within the communicated established time period. Present feedback in a professional and organized manner, which may include targeted resources to support student understanding. Model the appropriate and acceptable ways in which students are expected to communicate and interact online by maintaining a visible presence within your online course.

Response Time and Grading Expectations

Establish patterns of course activities. Patterns allow learners to develop plans of study specific to the cadence of the course. Enhanced course structure with a predictable pattern of operation and sequencing of events provides the learner with firmer foundation for growth. Established course related patterns reduce stress and frustration on the part of the learner. When these patterns change, that stability is interrupted.

Adhere to stated guidelines in course policy and syllabus. If any expectations are changed, this needs to be communicated as an announcement to all students and posted visibly throughout the course. Communicating those changes ahead of time will help to reduce student anxiety about the upcoming course adjustments.

Provide students with a realistic instructor “work schedule” which informs them of the time constraints of your course related activities (i.e. “I will not answer emails on Saturdays or Sundays”, “I will respond to your inquiry within a 24-48 hour period”) If the instructor cannot provide a detailed response within the stated time frame, the instructor should respond to the student within one business day to note when a more detailed response will be provided.

One communication strategy is the use of a “frequently asked questions” section in your discussion forums where you provide answers to questions that you receive repeatedly from students.

In an accelerated 7-week online course, if the instructor is unable to log into the course for more than a day, the students should be informed. In emergency cases, instructors should notify students as soon as possible, provide information as to when they will return, and provide access to an “emergency contact” or teaching assistant during the absence.

Convert Face-to-Face Materials to Online Materials

When converting instructional materials from a face-to-face format to an online accelerated course format, the content should be enhanced to increase learning and interaction levels among students, while simultaneously encouraging online communication. Content can be enhanced by using a variety of technology tools from audio, video, graphics, blogs, wikis, podcasts and more.

Analyze PPT Content

After setting out the learning objectives for the course, you must perform a comprehensive analysis of the PowerPoint presentation’s content. Content analysis is a critical step in the conversion of the PPT file into a good web-based course, as it helps determine whether the content identified is sufficient for covering the learning objectives comprehensively.

Organize PPT Content

Once you perform a comprehensive content analysis, the next step is to organize the content so that it flows logically. You can do this by making a rough outline of the potential order of topics. If the content is too long, it can be split into smaller segments, each having its own objective. This helps the learner understand and remember the content easily. Then, map the content with the learning objectives that have been set to check that it is adequate in the context of a self-paced online course. You need to ask yourself if a learner understand what is being communicated with the information provided. If the answer is yes, then you are ready to move on to the next step.

Incorporate Learning Interactivities

Self-paced e-learning courses must ensure the active participation of employees if the learning process is to be successful. An effective way of doing so is by incorporating a variety of interactive learning elements in your course, such as drag and drop, selecting answers to questions, or clicking on images and numbers. Most learning resources in the PPT format do not contain online learning interactivities, as they have been designed for a trainer-led environment. Be sure to include digital learning interactivities in the design of your technology-enabled learning materials.

Prepare Content for Online Learning

- Be more narrative as you go through your PPT to help students better understand the material and send them the details in a document or outline.

- Reduce the font sizes so you can combine slides and reduce the overall file size. Students seated at a computer monitor can read many more words per slide than an audience seated 20 or more feet from a screen.

- Avoid overuse of clip art and animation effects. Not all of these will transfer well to the web, and they add download time. Use only the minimum required to convey the instructional message, and test these carefully.

- Consider your audience’s ability to access the information you are providing. For example, be sure to make a transcript available for hearing-impaired students when using an audio-narrated slideshow.

Find Key Learning Points

As you structure your course, think about what knowledge you want people to walk away with. Look at each topic you cover and try to identify at least 1-2 key learning points for each one. Once you’ve identified these, you can create short quiz questions to add throughout your course. Questions help keep your learners engaged and ensure they are retaining the information they need.

Keep It Short

A wall of text is intimidating for your learners. That means you need to review your presentation and look for slides with lots of text on them. Split these slides out into multiple course pages, keeping each page’s word count to 200 words maximum. Limiting the amount of text on each page helps to make your course mobile-friendly, as well as making it easier for your learners to absorb the information. If you feel like your course is still too text heavy, consider whether you could use images or videos to liven up your content.

Convert Your Course Interactions

Research has shown that student-to-student mentoring in online courses can be both encouraging and motivational to students.

Consider creating small designated study groups amongst your students at the beginning of the term. Give those groups a dedicated discussion area within the course space. Group work may be assigned to enable students to deal more effectively with the demands of the course’s demands and feel like part of a learning community.

Consider having small groups of students work together to explore case studies for quantitative reasoning. For more information on the use of case studies in quantitative business courses, take a look at Madison’s 2009 book, Case Studies for Quantitative Reasoning. It contains a total of 24 case studies, each of which highlights how numbers appear in day-to-day media. The text is broken into six broad mathematical topics, each of which includes any background mathematics necessary for reading. Each individual study includes warm-up exercises and follow-up questions that demand critical thinking.

Ongoing and sustained communication in an online course is a critical component in the exchange of information. The key is to promote and encourage different styles of participation that engage students. Facilitating the formation of student groups early in the course cultivates a culture of learning and reduces feelings of isolation.

Additional Resources

Bodily, S. E. (1996). Teachers’ forum: Teaching MBA quantitative business analysis with cases. Interfaces, 26(6), 132-138.

Bosch, N., Crues, R., Henricks, G. M., Perry, M., Angrave, L., Shaik, N., … & Anderson, C. J. (2018, April). Modeling key differences in underrepresented students’ interactions with an online STEM course. In Proceedings of the Technology, Mind, and Society (6). ACM.

Capone, R., Del Regno, F., & Tortoriello, F. (2018). E-Teaching in Mathematics Education: The Teacher’s Role in Online Discussion. Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society, 14(3).

Chapman, J. R. & Rich, P. (2015). The Design, Development, and Evaluation of a Gamification Platform for Business Education. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2015, No. 1, 11477). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

Cho, M. H. & Tobias, S. (2016). Should instructors require discussion in online courses? Effects of online discussion on community of inquiry, learner time, satisfaction, and achievement. The international review of research in open and distributed learning, 17(2).

Gokhale, A. & Machina, K. (2018). Guided Online Group Discussion Enhances Student Critical Thinking Skills. International Journal on E-Learning, 17(2), 157-173.

Goldfinch, J. (1996). The effectiveness of school-type classes compared to the traditional lecture/tutorial method for teaching quantitative methods to business students. Studies in Higher Education, 21(2), 207-220.

Gönül, F. F. & Solano, R. A. (2013). Innovative teaching: an empirical study of computer-aided instruction in quantitative business courses. Journal of statistics education, 21(1).

Koichu, B. & Keller, N. (2019). Creating and Sustaining Online Problem Solving Forums: Two Perspectives. In Mathematical Problem Solving (263-287). Springer, Cham.

Madison, B. L., Boersma, S., Diefenderfer, C., Dingman, S., Ellensburg, W., & Roanoke, V. (2009). Case Studies for Quantitative Reasoning.

Minichiello, A. & Hailey, C. (2013, October). Engaging students for success in calculus with online learning forums. In 2013 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) (1465-1467). IEEE.

Riggs, S. A. & Linder, K. E. (2016). Actively Engaging Students in Asynchronous Online Classes. IDEA Paper# 64. IDEA Center, Inc.

Rollag, K. (2010). Teaching Business Cases Online Through Discussion Boards: Strategies and Best Practices. Journal of Management Education, 34(4), 499–526. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562910368940

Swart, W. & Wuensch, K. L. (2016). Flipping quantitative classes: A triple win. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 14(1), 67-89.